Where did Do No Harm Come From?

It came from you and thousands like you. Thousands of people who saw that their efforts were not having the impact they wanted to have. They struggled to find solutions and often they succeeded. Do No Harm is the record of their—of your—success.

Local Capacities for Peace and Do No Harm

Do No Harm began in 1993 as the Local Capacities for Peace Project (LCPP). Many, many colleagues in humanitarian and development work saw aid being used to support local populations in their efforts to escape conflict and to build their own peace. At the same time, they also saw aid being co-opted, misappropriated, and misused. Conflicts were being made worse by the presence of assistance.

They wondered how best to support the positive efforts while avoiding the negative impacts. The learning project, therefore, was twofold. How does aid exacerbate conflict? And how does aid mitigate conflict?

At an early workshop of the LCPP a physician participant said, “This project is like ‘do no harm’ for aid workers”. The phrase resonated became the title of the first booklet of early findings and questions that emerged from the case study phase, Do No Harm: Local Capacities for Peace, written by Mary Anderson. “Do No Harm” stuck precisely because that doctor was right: we were plumbing the do no harm principle for practical lessons about how to put it into practice.

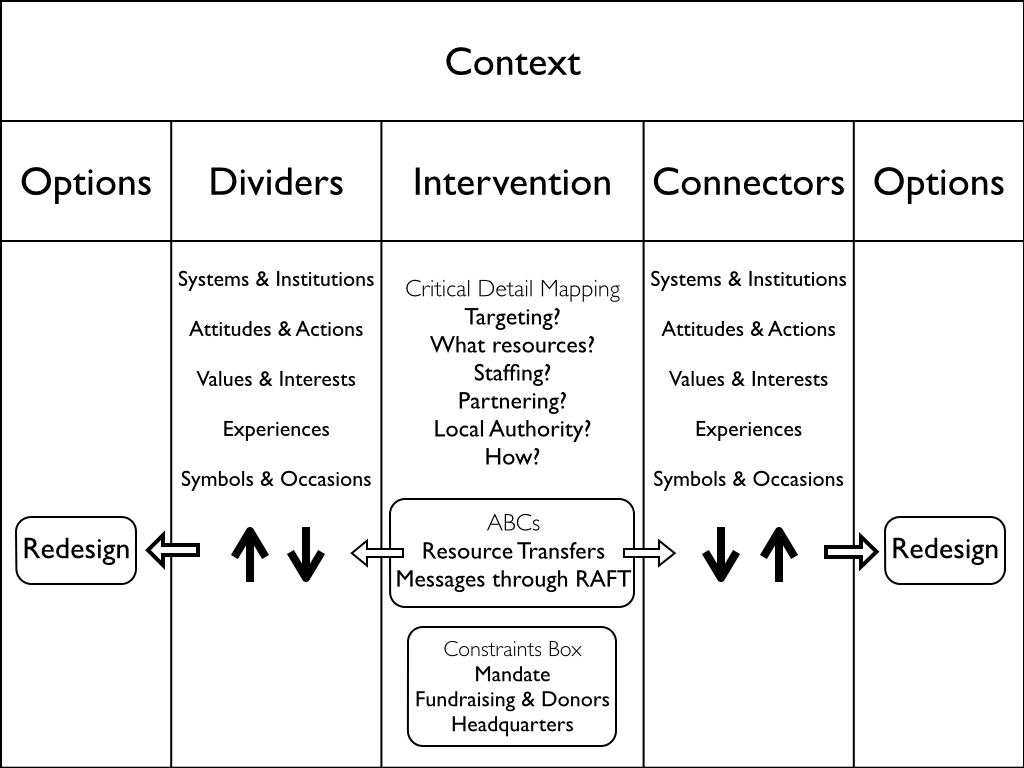

Mary used the title again for the 1999 book, Do No Harm: How Aid Can Support Peace—Or War. This book gathered the lessons from the feedback phase of the project, introduced the first Do No Harm framework, and propelled the project into the implementation phase, where the Framework would be used and tested.

The third major publication of the LCPP came out in 2001, Options for Aid in Conflict, gathering the lessons from the implementation phase, where organizations had been rigorously and continuously applying the Do No Harm Framework.

The LCPP was renamed the Do No Harm Project in 2001, due to colleagues in several countries telling us that they could not be involved in a project that had the word “peace” in its name. They had been calling the project “Do No Harm” for years already. The Project merely formalized it at that point.

Also published in 2001 was a training manual for Do No Harm that was based on the lessons from the implementation phase and Options.

The Do No Harm Project carried on working directly with organizations to transfer the lessons, help them think about their work, and make using Do No Harm a reality. We worked with hundreds of organizations and thousands of practitioners in over one hundred countries. Everywhere I go, I find people who know the concepts and who often have done something amazing with them.

Beginning in 2006, the Do No Harm Project began a formal process of visiting colleagues and organizations who had been involved in Do No Harm to learn what, if any, difference Do No Harm had made in their work. A new set of case studies was conducted, followed by feedback.

This Guide and the book, From Principle to Practice: A User’s Guide to Do No Harm, is the result of all these efforts over the past twenty years.

A Better Way

The Do No Harm Project explored the relationship between humanitarian and development aid because so many people in the field and at headquarters and among the donors saw negative impacts day after day. They said there must be a better way.

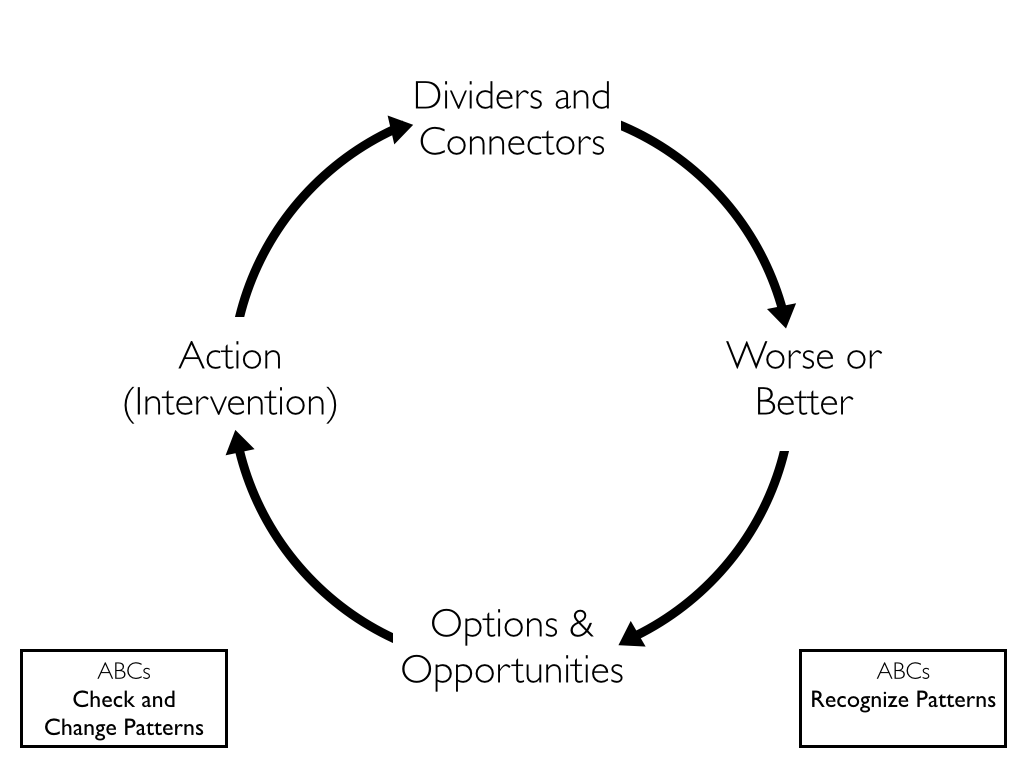

Over the past twenty years, the Do No Harm Project has documented the relationship between interventions and conflict. Beyond that however, we have documented the efforts by thousands of people to shift a negative set of patterns to a positive set. The first phases of the Project learned how aid had negative impacts and began the exploration of what we could do. For the past twelve years, as more and more people have taken up these concepts and worked with these techniques, the Project has explored what works.

Over 100,000 humanitarian and development workers at all levels and across the world have been trained in Do No Harm techniques. We have lost track of all the threads of this work because it is too vast and people are making it their own.

The Do No Harm Project had the privilege of visiting with thousands of creative and thoughtful people. We have learned these lessons from them. We will continue to learn them from you.

Previous Page Shared language and explaining Options

Next Page Collaborative Learning Methodology

Related Topics

Where does this Guide come from?

Acknowledgement

Do No Harm

The Project